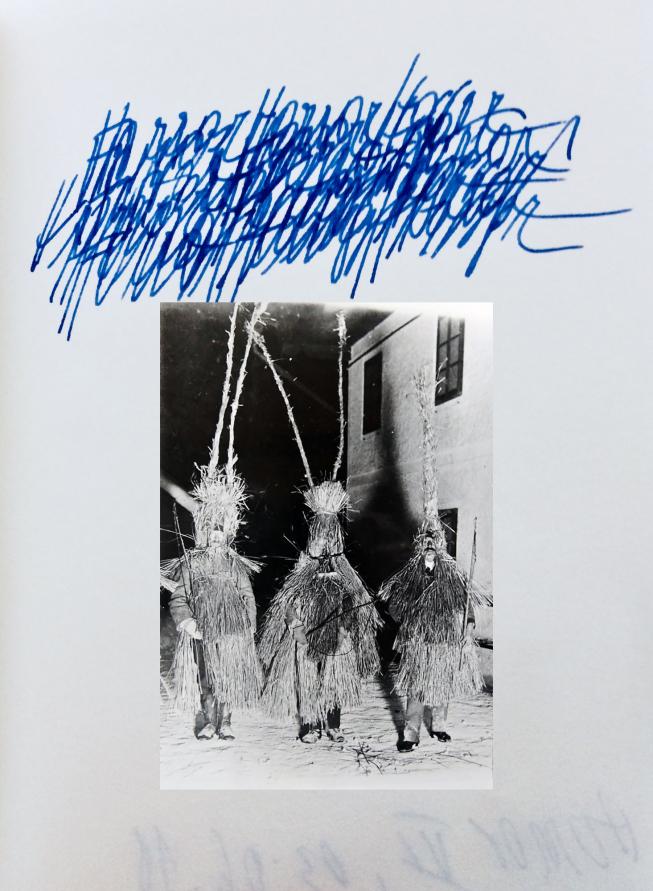

The process by which public space is modernized and subsumed under capital “may later spawn who knows what,” Siegfried Kracauer writes in 1930, “—perhaps fascism, or perhaps nothing at all.” With this thought-image of political contingency in mind, and faced with recent phenomena of nationalist-authoritarian governance, this presentation deals with horror film today—in a broad sense and from a political perspective. Mad Max: Fury Road, It Follows, Der Nachtmahr, Get Out: films such as these maintain the very “fascism, or perhaps nothing at all” when it comes to the people, to popular forms and fronts. As a type of cinema that makes experiences of systematic social insecurity perceptible (makes them thinkable while we break out in a cold sweat), horror films—at least those that take seriously the fun to be had in fear—depart from the fact that the political articulation of societies is a who knows what, because it is disputed. The stakes of this dispute are high when fascism knocks on the door (as if in a home invasion shocker). If this knock comes from outside, what is inside? While current NeoNazionaLiberalism wants to fill this inside with people as Volk (in the ideological sense of a pre-given whole), horror film—Volk-horror—maintains the hole. There’s nothing wrong with the Volk, but a lot is wrong with its fullness. The hole is revealing (in its affinity with truths): it allows insight into “hidden abodes of production”—where society is reproduced in the flesh, as in the body horror of the 1980s (Cronenberg, Society)—or into racist ideologies as in Get Out. Ultimately, maintaining the “hole in finitude” (Alenka Zupančič) in a horror mode means that—even with Maximum Madness and Fury—we cannot get rid of ideas: among them, ideas of justice, with which the Volk has to (con)front itself in a manner other than that of the Frontex-Fortress.

Volksfronten

“Perhaps fascism, or perhaps nothing at all”: Horror film as maintenance of the hole in the people (and vice versa)

Drehli Robnik, Vienna-Erdberg

Drehli Robnik is a film and political theorist, essayist, edutainer. “Lives” in Vienna-Erdberg. Research on public imaging of political power relations/subjectivations (film, pop music, public history). PhD Amsterdam University. Editor of Siegfried Mattl’s film writings (2016). Recent monographs: Film ohne Grund. Filmtheorie, Postpolitik und Dissens bei Jacques Rancière (2010); Kontrollhorrorkino: Gegenwartsfilme zum prekären Regieren (2015); DemoKRACy: Siegfried Kracauers Politik*Film*Theorie (2019).